Author’s Note: This is an edited version of the post I published on 22 March, 2025. Why, do you ask, did I make changes? The answer is simple: Oral history has its limits, in that it can only reflect what the teller of the story was told. I sent the post to my cousin in Germany - the cousin featured in the story - after I posted it; it turns out, I should have done so beforehand. She corrected some errors, added some details (including a photo), but most importantly, filled in some bits that my mother did *not* tell me, including the fact that our grandparents were apparently far more enthusiastic about National Socialism than my mom had led on. My cousin’s information came from her own mother (Eva in the story below), who was not on the greatest of terms with her mother-in-law and had less of a motivation to ignore - or gloss over - certain things than my mom might have had. None of the changes affect the central points of the piece, about the impact of fascism’s lies and my mother’s journey to seeing them for what they were; if anything, they reinforce both.

___________________________________

I was born in Düsseldorf, West Germany, ten years after the end of WW2 and the passing of the Thousand-Year Reich, Adolf Hitler’s declared attempt to make Germany great again.

The war itself was an ever-present constant in my childhood, from the bomb-shattered buildings - when I learned to count, fourteen remained just along the tramline to downtown - to the water-filled bomb craters near the bridge across the Rhine, where we fished for tadpoles. We used to dig up the sandbox in our playground to make mud; the Rhine was less than a kilometre away and we only had to go down a foot to strike groundwater. One day when I was five, the River ran unusually low, so we had to dig a bit deeper and found parts of an unexploded bomb; our entire block was evacuated.

Encouraged by my mom to read from the age of four, I lived for the library and spent hours browsing the shelves on the children’s floor. I loved the smell and sight of books. At first, I went with my older cousin, Bärbel, who would faithfully sign out three illustrated books for pre-school me and two chapter-books for herself. The day I turned six, old enough to register for my own library card, my mom gave me money for the streetcar and sent me downtown, confident I could find the way on my own. I wasn’t scared; I was thrilled - this was the best birthday present I could have asked for: independence! My unaccompanied arrival caused a bit of a sensation, but I got my card and my full entitlement of five books.

My mom did anything and everything to encourage me to read. She’d leave books lying around, knowing I would pick them up; I read National Geographic before learning English in school and "Gods, Graves, and Scholars" at age ten. I was particularly fascinated by books about the indigenous peoples of the Americas, devouring histories of the Inca empire and biographies of famous chieftains. When my neighbourhood gang played “Cowboys and Indians”, I was “Cochise” and in charge of cultural authenticity (of course, we didn’t call it that then).

Reading, my mother always taught me, was important. Learning about the world, about geography and history, was important. I learned exactly why she thought that, when I was fifteen years old.

Inge Nölke, my mother, was born in 1923, at the height of rampant hyper-inflation in Germany when her father would bring home his earnings in large shopping bags. She was the middle child and only girl. My uncles, Hans-Julius and Günther (nicknamed “Puck” for his impish personality), were born in 1921 and 1926, respectively.

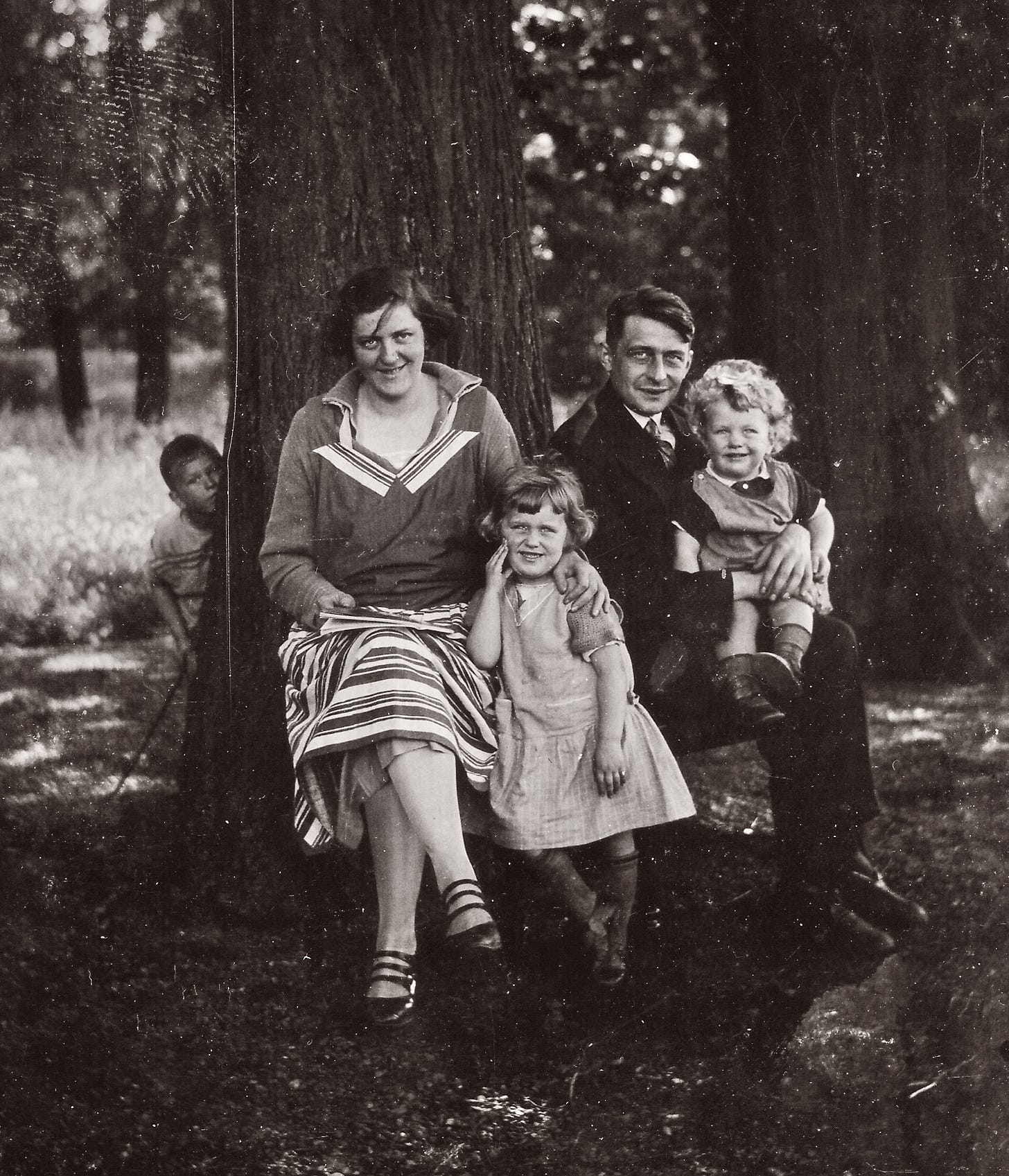

Hans-Julius, Erna, Inge, Franz and Günther Nölke, ca 1928

Their father, my grandfather Franz, was a WW1 veteran, as was his brother, Joseph. Together, they fought in the Somme until Franz was gravely injured and taken POW by the French. A third brother, Julius, was killed in action. After the war, Franz worked as a mid-level public servant in the health insurance system. He and my grandmother Erna lived in a one-bedroom-plus-den apartment, with an additional bedroom and toilet under the mansard roof, in a co-op complex newly built by Düsseldorf’s socialist government. German tenancy laws allowed them to pass the lease to their children and the apartment would remain in the family for almost 70 years. The Nölkes grew fruit and vegetables in the garden behind the apartment; the basement shelves were always lined with sun-filled jars of peaches or pears. I make preserves to this day, albeit with Niagara fruit.

Hitler was made Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, when my mother was nine years old.

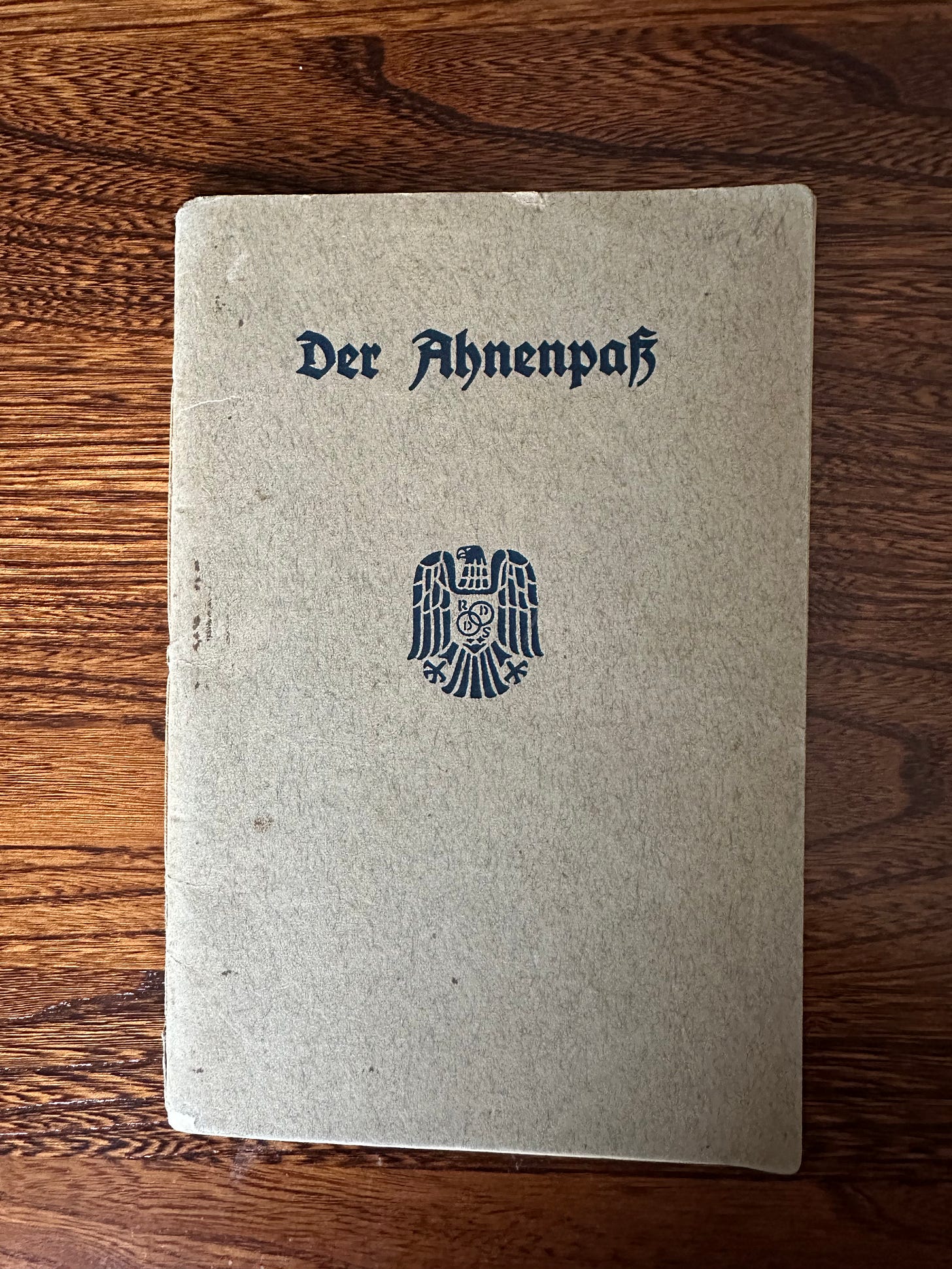

On April 7, 1933, two weeks after the Enabling Act, which in turn had followed the February Reichstagsfire, granted Hitler full powers, the National Socialists passed a law on the Reconstitution of the Public Service. It required public servants to prove their racial purity or lose their jobs. Erna dutifully embarked on completing the pages of the Ahnenpass (“ancestral passport”). Luckily, the Nölkes had never strayed far from the Lower Rhineland - I’m very much an aberration - and Erna managed to trace her husband’s ancestors all the way back to 1751, all entries confirmed by the requisite stamps from churches and official registries. The appearance of the name “Bloemenkamp” caused a momentary panic but turned out to be Dutch, not Jewish. The Ahnenpass was inspected and found in order; Franz was allowed to keep his job. I found it in a box of papers and old photographs when my mother passed away in 1980; even though I kept it as a sort of genealogy, it gives me the chills:

___________________

Der Ahnenpass – “the ancestral passport”.

The opening paragraph (of the 10-page introduction) reads as follows:

Racial Principle - … it is the highest duty of a people to keep its blood pure from foreign influences and to eradicate such foreign blood intrusions as have entered the national body... .

______________________

Although Franz was now confirmed as a proper Aryan, the goal posts for public servants moved again in 1934: now, they needed to demonstrate their loyalty to Hitler by joining his party, the NSDAP. Having spent years getting shot at in the trenches thanks to the decisions of incompetent rulers, Franz had little interest in party politics and had not joined the Party, despite being sympathetic to its goals for Germany; but now he needed that pin on his jacket if he wanted to feed his family. A friendly colleague in charge of the “recruitment drive” at the office backdated Franz’ membership card to 1932, to make it appear that he had joined before Hitler formally took power.

Franz took the party pin – eagle, swastika and all - off when he put on a uniform again in 1945 (about which more below). My mother kept it in the aforementioned box, but I couldn’t bring myself to take it to Canada after she died - there are limits to what one keeps as family memorabilia and a thing with the eagle and swastika went way beyond those. I have no idea where it ended up; my mother’s estate was bankrupt and I had to leave all but a few things to the Public Trustee.

With Franz’ job secure, life went on. The economy got better and the children grew; both Franz and Erna were happily swept up in The Führer’s vision for Germany. All three siblings joined the Hitler Youth – the “League of German Girls” in Inge’s case; membership became mandatory in 1936 but I don’t know when they joined, or with what level of enthusiasm. What I do know is that while Inge’s hair turned near black in her late teens, it was still on the blonder side while she was in the “BDM” and she was often picked to carry the Nazi flag in parades.

Classmates started to disappear from school and families from neighbourhoods; rumour had it they’d moved abroad. Parents and children alike learned not to ask questions, even as the answers stared them in the face. Today, there are “Stolpersteine” (“stumbling stones”) in the sidewalk in our block of Volmerswertherstrasse, marking where Jewish families had lived before being murdered by the Nazis.

Hans-Julius, Inge and Günther in their Hitler Youth uniforms, ca 1937-38

And then, Hitler’s ideas about “greater Germany” took the inevitable turn.

On 12-13 March of 1938, Nazi troops rolled into Austria and annexed the country in the name of bringing it “home” into the German Reich. A month later, Austrians formally welcomed the annexation (the “Anschluss”), by some 99.7%, in a referendum of dubious validity carried out under the watchful eyes of Nazi troops. In October that same year, Hitler claimed the Sudetenland - on the basis that its population was ethnically German - with the acquiescence of Great Britain, France, and Italy. Czechoslovakia, whose territory it was, was not invited to the consultations.

But Hitler’s appetite for territorial expansion (“Lebensraum”) was not yet satisfied. On September 3, 1939, his troops invaded Poland, triggering World War 2.

My uncle Hans-Julius, the eldest son - named after the lost brother - had always dreamed of flying. He had joined a gliding club in Düsseldorf at fifteen, becoming a youth gliding champion at the national level. When the war broke out, he saw his chance to become a pilot for real and joined the Luftwaffe, out of high school and before earning his leaving certificate. Public records show him flying on the Eastern Front starting in 1943, where he was awarded the Iron Cross twice - 1st and 2nd class - and was credited with downing three Russian fighters before being shot down near St Petersburg (in the “Oranienbaumer Kessel”). He was declared “MIA” in January 1944,

Hans-Julius Nölke on the Eastern Front (1943)

My mother, as “the girl” in the family, was not allowed to go to high school; the idea for her was to marry and become a housewife. To that end, she left school in 1939 after Grade 9 and enrolled in a home economics course. She turned into a pretty good cook – I still use many of her recipes – but she was bored to death. With no husband on the horizon, she obtained her parents’ permission to enrol in an English language course to become an interpreter, a profession suddenly much in demand. I don’t know what role her Father may have played in her decision; Franz himself had expressed the ardent desire to assist in the war effort by becoming a military translator, but failed. He had taken language courses to that end but flunked the competency exam; in a letter of 30 July 1942, a copy of which my cousin sent me, he can be seen begging for another chance because he felt he had not contributed enough to Germany with his WW1 service.

Left to right: Günther (16), Erna, Hans-Julius (21), Franz, and Inge Nölke (19), on the eve of Hans-Julius’ deployment to the Eastern Front, ca 1943

Presumably with her parents’ blessing, Inge practiced her language skills by listening to the BBC in the evenings, both the family radio and her head covered under a thick blanket to muffle the sounds as neighbourhood snitching was rampant. At night, the family huddled in the root cellar during bombing raids. Based on what she heard on the BBC, as opposed to from official reporting, she realized the war wasn’t going well.

Like virtually all official documents, Inge’s new certification - carefully preserved in that cardboard box - boasted a photo of Adolf Hitler, applying a layer of Nazi politics to every aspect of life. Inge succeeded where Franz had failed, namely getting into the military radio surveillance service, the “Funkdienst”. And so, at the age of 21, she headed to the North Sea island of Borkum, to play a small part in the late stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

I have no memory of my mother telling me what she thought of the work she was asked to do, or whether it bothered her. But I do remember her story of how, occasionally, someone would come across frequencies that broadcast music. Not just any music: forbidden, ‘degenerate’ music - jazz. The other monitors would see a foot tapping, she said, and pretty soon people would pass the frequency around in whispers. I have often wondered how many ships may have escaped a U-boat attack, just because a roomful of young women preferred bopping along to Charlie Parker to passing along actionable intelligence.

While Hans-Julius was flying over the Eastern front and Inge listened to conversations on the North Sea, their young cousin Claus, son of Franz’ brother Joseph – “Onkel Jüppi” to me - was sent to the German countryside. Similar to the child evacuations in Britain, the Kinderlandverschickung was created to help children escape the bombings that were, by 1943, a regular feature of life in German cities. Except safety was an illusion. Thirteen-year-old Claus fell ill with scarlet fever and treatment was not available due to wartime scarcities. When he stopped writing, his parents simply assumed his letters weren’t getting through - until the mailman delivered a parcel to Jüppi and Grete’s door, containing a perfunctory letter of condolence and the ashes of their only child.

Claus Nölke, aged 4 (app.)

By early 1945, Franz found himself in the Volkssturm, the militia created by the Nazis in 1944 to supplement the depleted armed forces with young boys and old men. While I thought he had been drafted, my cousin tells me he had volunteered, possibly because in the event of his death Erna would be entitled to a widow’s pension, something a mere civil servant could not provide. By the spring of 1945 American forces had surrounded Düsseldorf and Franz was sent to defend the airport. Based upon the account of a colleague who served with him, on the second or third day Franz laid down his gun, left his position, and walked into the American gunfire. The colleague suspected he had suffered from “shell shock” - today we would call it PTSD - and experienced flashbacks to his time in the Somme; we can only speculate whether his wish to ensure Erna’s financial security might have played a role.

Franz Nölke in “Volkssturm” uniform, in front of the house on Volmerswertherstrasse (1945)

I’m not entirely clear on the details – 50 years is a long time to recall a piece of oral history – but my mother’s post-war story starts something like this: After British forces took Borkum, Inge and the other young radio operators and encryption workers were rounded up and moved to a consolidation camp for civilian prisoners, whence they were released in June or July to make their own way back home. Inge had become friendly with a young woman from Dresden, Eva Curth, who had worked in encrypting military messages on the now-famous Enigma machines. Eva’s younger brother, Helmut, had falled on the Eastern front, while her parents had perished in the firestorm that followed the allied air raids on the city in February 1945. With her family gone and Saxony under Russian control, Eva was at a loss; Inge invited her to come with her to Düsseldorf.

Together the two young women, aged 22 and 23, walked and hitched rides across the destroyed country for three weeks, not knowing whether the apartment where the Nölkes had lived was still standing. On their way through Düsseldorf they stopped at Franz’ office and it was there that Inge learned of her father’s death.

Günther (“Puck”) had been too young to be called up for most of the war. Not as academically inclined as Hans-Julius, he left school after Grade 9 for an apprenticeship on a farm. He got trampled by a horse, lost his left foot, and became exempt from the draft. But after word came of his brother’s disappearance in Russia, Puck volunteered and the depleted army accepted him, prosthetic foot notwithstanding. He was killed by Russian bullets during street fighting in Berlin, on May 7, 1945, the second-last day of the war. Erna claimed that she had seen her son in a dream that night, running and falling.

When Inge and Eva arrived at Volmerswertherstrasse, in the late summer of 1945, they found the house with the Nölke flat mostly intact, but with bomb damage in one corner and the den filled with water. Erna, who had spent the dying day of the war with relatives outside of town, had survived - malnourished and in ill health, shattered and bitter.

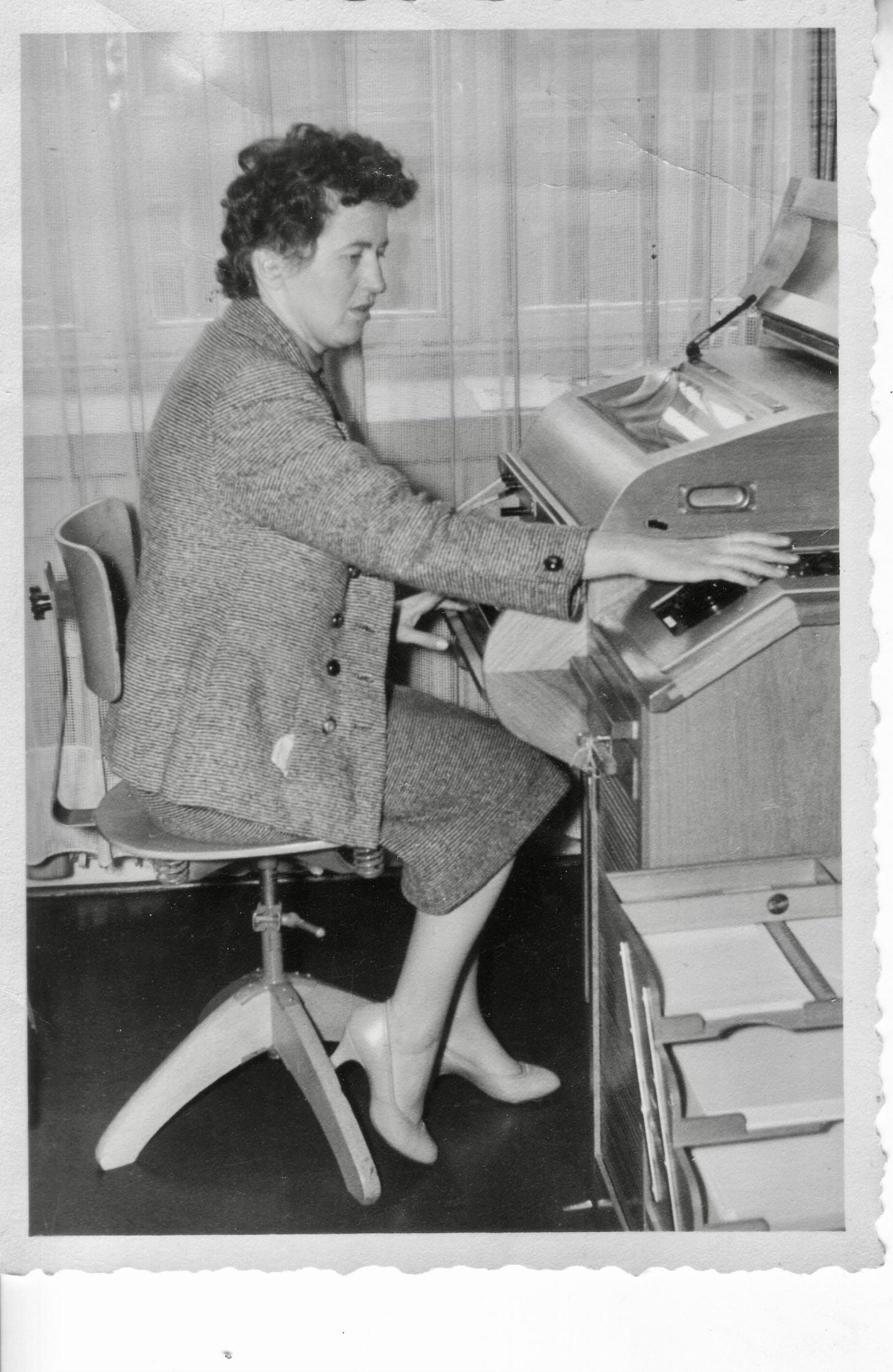

As luck would have it, Düsseldorf was in the British occupied zone. Given her ability to speak English, Inge quickly found work with the occupying forces and was able to put food on the table. Eva spent some time with relatives nearby but joined them as a subtenant, having found work with the City.

Inge Nölke, working for the British Occupying forces

By November of 1945, all radios on the British base were tuned into the broadcasts from the Nuremberg trials. People would taunt the small German staff about the impending fate of their former leaders, but Inge had ears only for the testimony. She had developed a healthy skepticism about the conduct of the war while listening to the BBC, but the information she learned here was new and at a wholly different level.

She learned about the atrocities that had been committed by people celebrated as models, leaders, and heroes. How the campaign against the Jews had led to mass slaughter, conducted in the name of the German people - in her name. And how everything she had been told to believe, everything that had triggered and moved and shaped the events of the last twelve years, had been a lie.

My mother started to buy history books, which were slowly becoming available again after over a decade of selective suppression. She asked her co-workers about books in English when she ran out of German ones to read and brought home any and all newspapers and magazines she could lay her hands on. Inge read anything and everything that offered new perspectives about the things she had been taught. She read even such unlikely tomes as Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico, just to get the Romans’ view of what the Germanic people had really been about.

Years later, when the GDR started permitting visitors from the West, she crossed the Iron Curtain to visit a childhood friend in Saxony. The GDR forced West German tourists to exchange “Deutsche Mark” for Eastern marks at par. With nothing useful to buy with that money, she went to a bookstore to get me collections by my favourite poets - Rilke, Heine, Morgenstern - only to be told, one after the other, “We don’t sell that here.” When she asked the clerk what they did sell, he said, without skipping a beat, “Well, we do have the Collected Works of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin…”. So she brought me back one of those, a brick in tiny font and thin paper, with the sardonic observation that in the East things obviously hadn’t changed all that much.

While working for “the Brits”, Inge caught the eye of a Sergeant named Steven. Their plans for a future together ended when his family recoiled at the idea of their son bringing a German home with him. Her heartbreak was soon mitigated by a letter, heavily censored, that arrived via the Red Cross: Hans Julius was alive, in a POW camp somewhere in the Siberian taiga.

Exchanges of mail took months, but Inge and Erna were able to tell him about Franz, Günther, and Claus. And about the girl from Dresden, who was now living with them. “If she is pretty,” he joked in a return letter, ever the cocky flyboy, “maybe I’ll marry her.”

Hans-Julius came home in 1949. Having nearly completed high school, still a relative rarity then, he had been headed for post-secondary education, but there was no GI bill for returning German POWs. There was, however, a lot of rebuilding to be done and thanks to his experience building glider planes, he quickly found an apprenticeship position as a carpenter. Perhaps inevitably - and apparently deeply resented by Erna - he and Eva fell in love, married, and had a daughter in 1951, my cousin Barbara (“Bärbel”).

With the help of the Red Cross, Eva discovered that her younger sister Magda - twin to the brother lost at the Eastern Front - had survived the firestorm and made it to Frankfurt, in the American zone, ahead of the Russians. They would both spend the next several decades sending care parcels of coffee, tea, chocolate, and nylons to relatives trapped in the “socialist paradise” of the GDR. Magda suffered from lingering PTSD, for which she refused treatment even as it became available towards the end of her life.

Erna died in 1953, adamantly declaring herself a “proud Nazi” until the very end.

When the new Federal Republic of Germany created its own airline, Lufthansa, Hans-Julius tried to qualify as a commercial pilot but was refused due to his colour blindness. This had never been an issue when he’d flown fighter planes; now, it served as a severe blow to his dreams of a better life.

Inge found more lucrative work with a small law firm, whose principal was half British on his mother’s side and had been certified as fully “de-nazified”. Heading up the only English-language capable firm in Düsseldorf, Herr Galler attracted an astonishing number of American – and later Japanese - Fortune 500 firms, looking to establish commercial bridgeheads in a slowly recovering Germany.

Enjoying her relative financial independence, Inge went on a winter holiday in Northern Italy, where a fling with a handsome skiing instructor resulted in a surprise pregnancy – at a time when unwed motherhood was still frowned upon. But the shortage of men in Germany made marriage unlikely, Inge wanted to be a mother, and her brother and sister-in-law pledged their support. Inge had supported Eva when she had needed it most; looking after me while Inge worked full-time was her way of paying back that debt. I was born in December 1955 and given “Eva” as my middle name to honour my aunt.

For a while, things were good. Bärbel and I had a happy childhood in a household with three loving adults - unconventional perhaps, but not unusual in those post-war years. Life was modest, but we always had what we needed. Occasionally the doorbell would ring and there’d be a person disfigured or displaced by the war, looking for a warm meal. Eva and Inge always opened the door.

Hans-Julius, or “Papi”, as I called him, was my father figure and I have loving and warm memories of his presence in our lives. But there were shadows. He hated being near woods - they triggered “bad memories” from years of forced labour - and was happiest in wide open spaces. No longer allowed to fly, he built himself a sailboat and spent his weekends on the Rhine, teaching his daughter how to read the wind.

One thing that stuck out to me even as a young child was that, during the rare times when Papi talked about his POW years, he always spoke positively about his Russian guards. One of them, a young doctor, had saved his life by sharing her bread rations when he was near-death from tuberculosis. “None of them wanted to be there, either,” he would say. “They were in the same position as us.”

Seeing an opportunity in 1965 to get into the new field of electronic data processing, Hans-Julius applied for re-education assistance, but was rejected on account of his age (he was 44). The week he got the notice, he took on a project out of town, rented a room in a small motel, and hanged himself. “Heart attack,” Bärbel and I, aged thirteen and nine, were told.

My mother fell into a deep depression and started drinking; she was a slip of a thing and it didn’t take much to knock her out. She took time off work for a few months for what the doctors called a nervous breakdown. We had moved out of the mansard room in the family apartment by then, into a flat of our own. I took refuge in books, as did my mom. She was on disability but there was always money for books, or for streetcar tickets to the library. By early 1966 she was back at work; with Eva now also back in the workforce, my cousin and I became latchkey kids.

Encouraged by my mother, I started to spread my wings. Like her, I loved the English language and started listening to the pirate broadcaster, Radio Caroline, or the US and British Forces’ networks. I went through a brief communist phase that culminated with a poster of Che Guevara - whom Inge called “that jungle Jesus” - on the wall of my bedroom. I took it down after I tried to read The Bolivian Diaries and found it to be impenetrable nonsense. I turned to protest songs and went on my first demonstration - against the Vietnam War - at thirteen.

When Nixon came to Germany in 1969, with much fanfare, I wrote on our school blackboard during recess, “Make Love Not War!” and our head teacher called my mother into school. Inge yelled at her, asking whether we should prefer war to love, and hadn’t we Germans learned anything? The teacher called in sick for the next two days; my transgression was not mentioned again.

My revolutionary fervour petered out with a poster of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” in the place where Che had once hung. The Vietnam War notwithstanding, I was in awe of all things American.

Through it all, my mother encouraged me to think, read, watch, and listen to whatever caught my fancy; she never judged, but always read what I read so we could talk about it. We watched war movies, including The Longest Day in the cinema twice, and agreed that it was a Good Thing the allies had won.

When I was fifteen, Judgment at Nuremberg premiered on German television. It was advertised for days beforehand; the ads made clear that this film was not suitable for children. My mom’s response was to help me build a nest of cushions in front of the TV; it would be a long movie, she said.

“This is important,” she said. “We need to see this.”

The movie marked the first time either of us saw actual cinematic footage from the concentration camps. The images haunted me for weeks. I asked my mother if she had known about these atrocities while growing up, or while she did her wartime service. She said no, very emphatically - she’d had no idea. Nobody in her family had - not until she heard about the Nuremberg trials on the radio.

“They lied to us,” she said. “They lied about everything.”

Not long thereafter, she started spiralling again. My aunt Eva became my rock when things got bad, when Inge was just sitting silently in her chair, drinking and reading, one eye closed to stop herself from seeing double. Whenever I asked her why she drank, or why whatever I tried to get her to stop wasn’t enough, she would break down and cry.

Sometimes, though, she would go on a tear, about how everyone in their family had suffered and died. She told me of Hans-Julius’ suicide; about the cruelty of little Claus’ death and how it had broken his parents; about Puck, who should never have been a soldier; about her father, who went back into the trenches to die; about her mother, who had withered away, a bitter and angry woman.

Time and again, she would repeat the same phrase:

“They lied to us.”

Inge Friederike Josephine Nölke died on October 10, 1980 at age 56, of complications from cirrhosis of the liver. I was already living in Canada, having met my husband while on a student exchange that I applied for in order to get away from the depressive atmosphere of my home. I flew home as fast as I could when Eva called me but arrived too late to say goodbye. At the funeral, I met an elderly uncle, a cousin of Franz’ and Joseph’s, who congratulated me on not having changed my name upon marriage, unlike my cousin. According to him, apart from him I was the only Nölke left in the “protestant” branch of the family.

Two years later, I started law school. I ended up joining Canada’s foreign service, where I worked on atrocity crimes, human rights, the law of armed conflict, and international peace and security. Now retired, I continue to read voraciously on politics and international affairs, drawing on as many diverse sources of news as I can to sort facts from ideology, assess agendas, and triangulate the truth through the spin.

My mother’s most precious gift, wrought from the ashes of our family – and one which I have since tried to pass on to my own daughter - was to make sure we would be equipped to see through the lies.

Hallo Frau Nölke,

although I am considerably older than yourself, your story and that of your mother whose first name I share are surprisingly similar to mine: bombs and air-raid shelters, in my case in Siegen not that far from Düsseldorf, scarlet fever and diphtheria, 7 years old in 1945, relatives in East Germany, one relative a “Spätheimkehrer” after eight years as a prisoner of war in Russia, my enthusiasm for languages, studies in Germersheim to become an interpreter/translator, work in England and emigration to Canada in the sixties, 40 years in Ottawa (where I suppose you lived at some stage or perhaps still live). British translator husband worked for the Translation Bureau of the Federal Government, I freelanced most of the time and brought up three children. Retirement in Toronto to escape the terrible winters. Two children still in Ottawa whom we visit as often as possible.

I, too, remember “they lied to us”, but I am now going through feelings of betrayal and disappointment, because this time THE AMERICANS, one could even claim “most Anglo-Saxons” (see Brexit), lied to us when they preached democracy and freedom after the war and left us, even myself at age 7, with terrible feelings of guilt and being unworthy, having to repay something, make up for something, and with the urgent obligation to “make the world a better place”.

I even have a sneaking suspicion that you are making a similar connection. If this is the case, it would be absolutely fascinating to hear from you how you are dealing with this. I am shocked and very very angry and frightened. I am trying to get my German citizenship back which I lost when I became British (and later Canadian), hoping I have somewhere to escape to if, when, the assault and occupation from the South occurs. I HAVE LIVED IN AN OCCUPIED COUNTRY, which luckily was a relatively benign part of one, but I went on frequent trips to East Germany where most of my family lived, and the parallels are already showing up in the USA. I wish there was something practical for me to do, such as learning how to use a gun. I keep talking about and mentioning a “militia of angry grandmothers”, and I am only half joking. I find other older women agreeing with me. We would be the most likely to be made to suffer under a Trump regime of sadistic misogynists, equalled by the plight of our granddaughters.

I shall keep following you, and who knows, I might bump into you one day, maybe even in Ottawa. Thank you so much for telling your story and touching a chord. So many similarities!

Grüße,

Inge Jordan

Dear Sabine,

I have just received the blessing of reading

your loving account of your family and you.

Every word moves me deeply.

You honor them all

as you share

their courageous and painful lives

so truthfully and mercifully with us.

I wish we were neighbors.

I would invite you over

for coffee

and we would talk about then

and now.

How they lie to us.

I study the sickness of lying

and write about it.

I feel deep kinship

with your Mom and you.

Thank you for all the time and work

and love you devoted to writing

your story of all you hold dear.

How your beautiful mother raised you

to transcend all limits she faced.

Deborah